The Prince of Sansevero Life

An enlightened prince

Raimondo di Sangro Prince of Sansevero (Torremaggiore 1710 – Naples 1771) was an original exponent of the first European Enlightenment. A brave soldier, man of letters, publisher, first Grand Master of Neapolitan Masonry, he was – above all – a prolific and enterprising inventor and patron. In the underground laboratories of his palace, in Largo San Domenico Maggiore, the Prince dedicated himself to experiments in the most disparate fields of the sciences and the arts, from chemistry to hydrostatics, from typography to mechanics, obtaining results which appeared “prodigious” to his contemporaries. Because of his mainly esoteric conception of knowledge, di Sangro was, however, always reluctant to reveal the “secret” details of his inventions.

Raimondo di Sangro’s masterpieces

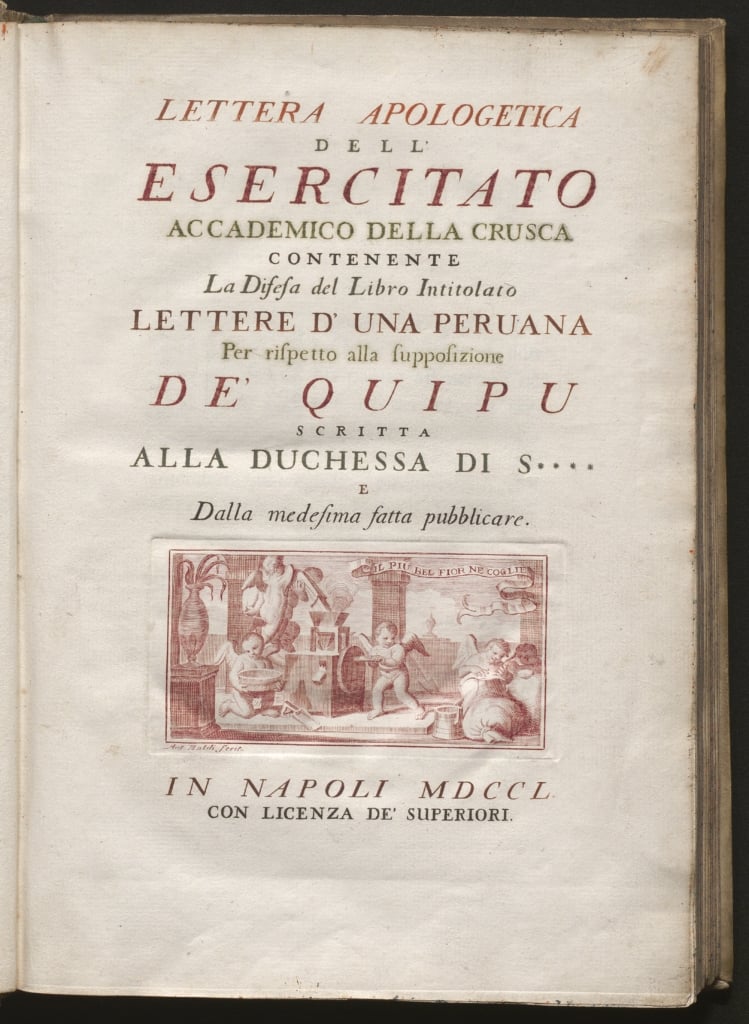

His intellectual output has therefore passed to posterity above all thanks to the rich symbolism of the Sansevero Chapel, a glory of world art, of whose impressive iconographic design the Prince was the ingenious creator. Part of his output was also committed to writing, especially the Lettera Apologetica, a work which caused a stir both on account of its typographic excellence and its controversial subject matter, so much so as to be judged “a sink of heresy” and, as such, banned by the Church of Rome.

A man becomes a myth

Sometimes considered a successor of the alchemist tradition and a “great initiate”, other times an interpreter of the emergent modern science, Raimondo di Sangro fed a veritable myth about his own person, which would last throughout the centuries. With his multifaceted activities, still today wrapped in an aura of mystery, he embodied the cultural ferments and the dreams of grandeur of his generation. The inscription on his tomb describes him as an “extraordinary man, gifted in all he dared to undertake […] a famous investigator into the most recondite mysteries of Nature”.

Testimonials of an extraordinary life

To understand the historical and artistic, spiritual, and philosophical message of the Sansevero Chapel, it is necessary to know the biography of its patron, Raimondo di Sangro, Prince of Sansevero. The main source for reconstructing the majority of his life, thanks to its wealth and precision of information, is the second volume of the Istoria dello Studio di Napoli (1754) by Giangiuseppe Origlia. The anonymous Short note on what can be seen in the house of the Prince of Sansevero is also essential reading (the first edition, of 1766, was corrected and enlarged in 1767), together with the works published by di Sangro himself, as well as the endless information in guides and reports for eighteenth-century travellers, not to mention letters, literary texts, and national and international archive documents.

Noble origins and early studies

Scion of a very high ranking household, he was born on 30th January 1710 in Torremaggiore, in Puglia, where the Sanseveros held the majority of their feudal lands. His mother, Cecilia Gaetani dell’Aquila d’Aragona (daughter of the Princess Aurora Sanseverino, a well known intellectual and protector of artists), died in the December of the same year. His father, Antonio di Sangro, Duke of Torremaggiore, was forced away from Italy for long periods of time for personal reasons. Entrusted to the care of his grandfather Paolo, sixth Prince of Sansevero and Knight of the Golden Fleece, at one year of age, Raimondo was transferred to Naples, then capital of the Austrian Viceroyalty, where his ancestors had settled in a remarkable palace in Largo San Domenico Maggiore. In Naples, he received his earliest education and began to study literature, geography and the knightly arts.

A quick and inquisitive mind

Very soon, however, it became clear that he had an exceptional mind. Origlia says that “his excessive brightness of spirit, and remarkable quickness” led his grandfather and father (home from Vienna around 1720) to send him to Rome to the Jesuit College, the most prestigious school of the time. Under the guidance of brilliant masters, Raimondo proved to be an excellent philosophy student and linguist (mastering at least eight languages), studying pyrotechnics and the natural sciences, hydrostatics and military architecture. On this subject, while very young, he wrote a still unpublished treatise. In the Roman seminary, he also became acquainted with the works and the natural history museum of Athanasius Kircher, famous scientist and seventeenth-century Egyptologist, whose writings were full of references to the Hermetic tradition.

His first invention and his move to Naples

1729 saw his remarkable debut as an inventor. As proof of his “marvellous intellect”, he projected, on occasion of a theatrical performance, an ingenious folding stage, which amazed even Nicola Michetti, Engineer of Czar Peter the Great. In the meantime, once his paternal grandfather had died, Raimondo came into the title and inheritance in 1726, thanks to his father refusing them. In this way, he found himself at only sixteen years old at the head of one of the more powerful families in the Kingdom. Having completed his studies in 1730, he lived in both Naples and Torremaggiore until 1737, when he took up permanent residence in Palazzo Sansevero, in the heart of the ancient centre of Naples, which had become the capital of the new Kingdom under King Charles Bourbon.

A wedding, high-ranking honours, and “new discoveries”

When the Prince married his cousin Carlotta Gaetani dell’Aquila d’Aragona, heir to many feudal lands in Flanders, Giambattista Vico dedicated a sonnet to them, and Giambattista Pergolesi set the first part of a stage prelude to music in honour of the couple. Because of the prestige and intimacy he enjoyed with the young sovereign, Raimondo was appointed Gentleman of the Chamber with Office to His Majesty and, in 1740, was raised to Knight of the Order of San Gennaro, a decoration reserved to a limited élite selected by the Bourbon Crown. With his mind always “applied to new discoveries”, he distinguished himself for his inventions. Already in 1739, he had in fact created an innovative hydraulic device and an arquebus capable of firing using powder or compressed air, which he donated to Charles Bourbon.

The Battle of Velletri and fame in Europe

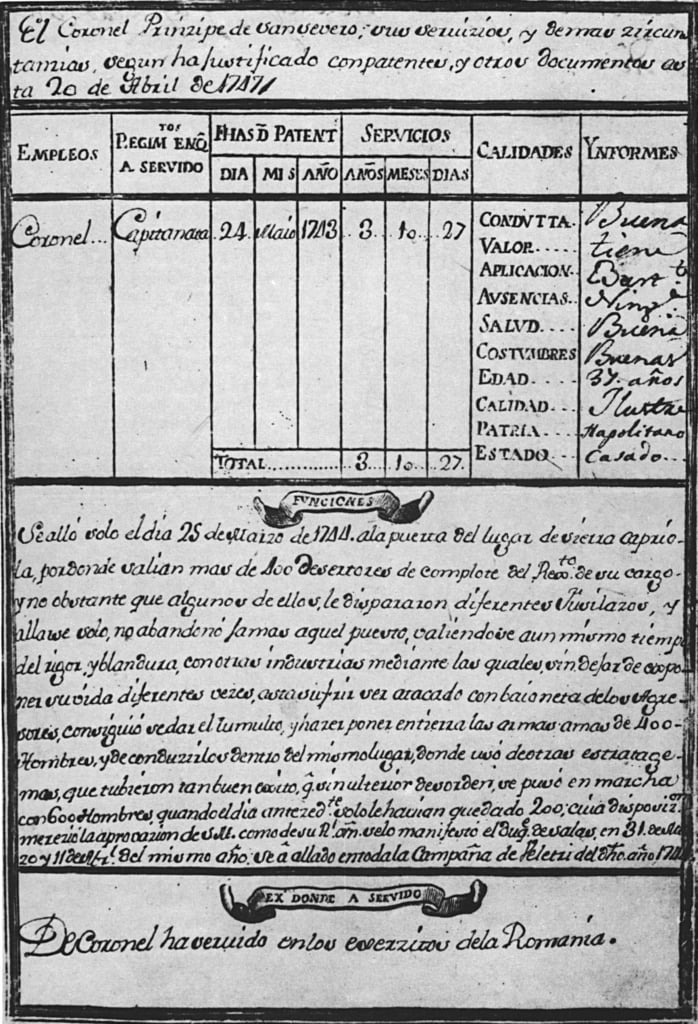

The forties and fifties of the eighteenth century were key years for Raimondo di Sangro’s fame, which grew and spread across the limits of the Kingdom. In 1741 he invented a cannon, which, compared with other examples of the same type, weighed one-hundred-and-ninety lb less and had a much longer range. He become colonel of the Capitanata Regiment, one of the twelve provincial units of the Bourbon army. He took part in the glorious battle of Velletri against the Austrians (1744), distinguishing himself for his courage and skill. His passion for the military art led him to publish his Practice of Military Exercises for the Infantry (1747). His competence in the subject earned him the praise of Louis XV of France and Federico II of Prussia, and all the Spanish troops adopted the useful exercises he prescribed.

Further experiments. The work on the Sansevero Chapel begins

Already admitted in 1743 to the Accademia della Crusca, the most authoritative cultural institution of the period, under the pseudonym of Esercitato, the following year, Raimondo obtained authorisation to read prohibited books from Benedetto XIV. So he studied the works of Pierre Bayle, the writings of the French philosophes and the radical Enlightenment thinkers, the texts of the alchemists and the Masonic tradition, and scientific treatises of all kinds. With his reading came the experiments: he put on spectacular firework shows with fireworks of colours never seen before and a perfectly impermeable material which he gave to the sovereign. He prepared a number of medicines which brought about unexpected cures and developed a method of printing polychrome patterns and characters with a single turn of the press, using typographic devices designed by himself. In the meantime, he started work on the Sansevero Chapel, which would last up to his death. In 1749, Francesco Maria Russo painted the fresco on the vault of the funerary chapel, using special colours produced by the Prince.

Masonic teaching and abjuration

In 1751, the Prince was at the centre of a “scandal” which seemed “the greatest in the world”. His innate curiosity, his eminently esoteric conception of knowledge and, at the same time, his mind open to the new ideas of the European Enlightenment had in fact attracted him to Freemasonry, a secret society through which many of those new ideas were being spread. Thus, in August 1750, Raimondo di Sangro became the Grand Master of the Neapolitan Lodge. With his Bull Providas of 18th May 1751, Benedict XIV had formally condemned the “worshipful company” in the name of the Church, a sentence furthermore reiterated in July with an edict of King Charles. The Prince had no other choice but to abjure.

The Lettera Apologetica on the Index of prohibited books

But his problems did not end here. At his typographer’s workshop set up in his palace, in 1751 (but dated 1750), he printed his literary masterpiece: the Letter in Defence of the Academician Esercitato of the Crusca containing his Defence of the book entitled Letters of a Peruvian woman concerning the hypothesis regarding the Quipu addressed to the Duchess of S**** and published by the same. Ostensibly focusing on an ancient system of signs (the quipu) in use by the Incas of Peru, the Lettera Apologetica touched on many dangerous subjects, citing a large number of unorthodox authors and spreading the innovative ideas of Masonry, if not also – according to the Prince’s opponents – esoteric messages transmitted using a secret code. Judged to be “a sink of heresy” and harshly attacked in various pamphlets, the work was banned by the Congregation of the Index of prohibited books, and not even the publication of a Supplication (1753) which the Prince sent to the Pope was enough to have the Apologetica removed from the list of the prohibited books.

Work in the laboratory and masterpieces of Baroque art

Disappointed and embittered, di Sangro threw himself into the “study of Experimental Physics”, and installed under his palace a great furnace and a chemist’s laboratory “with every type of burner”, making new and surprising discoveries, such as that of a mysterious “perpetual light”, about which he wrote a number of letters to the Florentine Giovanni Giraldi, later translated into French and collected into a volume addressed to the scientist Jean-Antoine Nollet (1753). Energy and money were above all invested in developing the iconographic design of his Chapel, bringing into being such masterpieces as Corradini’s Modesty, the Veiled Christ, and Disillusion.

A Wunderkammer in Naples at the height of the 18th century

The fervid mind of the Prince of Sansevero, who was “unable to restrict himself to only one subject”, continued to create wonders. His palace in Largo San Domenico Maggiore become a focus for academics and travellers on the Grand Tour, curious to see his exceptional inventions, whose secrets, however, he never fully revealed, including artificial gems and coloured marbles, paintings using the so-called “colori oloidrici” and wool (producing special optical effects), experiments in palingenesia, and desalinating sea water. These and many other experiments amazed his fortunate visitors. The so-called Anatomical Machines were disconcerting. Di Sangro kept them in his “Apartment of the Phoenix” (today they are displayed in the Museum). The complicated mechanism of a great musical clock which he had designed and situated on the small bridge which connected the palace to the Chapel also amazed all who saw it.

The project of a lifetime: the Sansevero Chapel

His genius also found expression inside the Chapel. In 1759, the long inscription dedicated to him was created using chemical solvents, and from the mid-sixties Francesco Celebrano worked on his sensational inlaid Floor Labyrinth, making use of a method di Sangro had explained to him. In the meantime, the allegoric-initiatic path of the mausoleum began to take shape, with the building of the other statues of the Virtues by Queirolo, Celebrano and Persico. As a demonstration of the care the Prince lavished on every detail of his wonderful project, in his will he urged his heirs not to modify anything in the order and symbolic arrangement he had conceived.

Relations with the Italian and European cultural elite

In 1756, he published his Dissertation sur une lampe antique, in which he returned to topics similar to those addressed in the letters on the perpetual lamp. Even though after this he would publish no other works, in order to avoid censure, his intellectual activity did not cease. He was also a member of the Società Colombaria, a scientific-literary academy in Florence, and was friend and correspondent of the illustrious exponents of the world of culture. Antonio Genovesi, a luminary of eighteenth-century thought, sent the last letter he ever wrote a few days before he died to the Prince. Fortunato Bartolomeo De Felice, enlightenment publisher active in Switzerland, kept in touch with di Sangro through his patron Vincent Tscharner. Giovanni Lami, editor of «Novelle Letterarie» in Florence, Lorenzo Ganganelli (later to become Pope Clement XIV), the physicist Jean-Antoine Nollet, and the geographer Charles Marie de la Condamine kept up epistolary exchanges with him. The astronomer Joseph Jérôme de Lalande, almost incredulous in the face of the culture and the personality of the Prince of Sansevero, commented that he “was not an academic, but an entire academy”.

Printed works bearing dedications to the Prince

More than one book was dedicated to him. In fact 1755 saw a reprint in a single volume of The Iris and the Aurora Borealis, two scientific poems in Latin by the Jesuit Carlo Noceti, with a parallel Italian translation. This edition, printed at the Imperial Press in Florence, opened with a long dedication to Raimondo di Sangro by the erudite Tuscan Anton Francesco Gori. In 1764-67, furthermore, the Prince of Sansevero financed a monumental edition in five volumes, which came out in Perugia, of the Iconologia of Cesare Ripa, an essential iconographic treatise published for the first time at the end of the sixteenth century.

Financial hardships, the last invention, death

The last fifteen years of his life were marked by serious economic difficulties, which did not however distract him from his interests and from the demanding completion of the Sansevero Chapel. After the departure of King Charles for Spain (1759), furthermore, his relationships with the Court worsened, as he was ill thought of by the powerful Minister Bernardo Tanucci and other important personalities, who had not forgotten the Masonic affair and little tolerated his aristocratic pride and intellectual unorthodoxy. In July 1770, lastly, he made his last spectacular public appearances. For a number of Sundays he crossed the waters of the bay, from Capo Posillipo to the Ponte della Maddalena, on an “sea-going carriage” of his invention, which proceeded quickly across the waves thanks to a cunning system of paddle wheels. Shortly afterwards, on 22 March 1771, he died in Palazzo Sansevero, thanks to – according to the sources – a disease caused by his “chemical preparations”.

An enlightened and controversial figure

Unconditionally loved or hated, sometimes considered a successor of the alchemic tradition and a “great initiate” sometimes an interpreter of the emergent modern science, Raimondo di Sangro left upon his death a myth that would be carried on throughout the centuries. The aura of mystery which still today, given the impossibility of marking the precise limits of his wide-ranging activity, surrounds the life and work of the Prince of Sansevero, must not however cloud the image of the refined intellectual, working in that fervent and fruitful age which was Naples at the time of Genovesi. He was the most representative and, at the same time, original exponent of the enlightened aristocracy, active in society, one of the first to read the signs of evolving history and to favour the civil renewal which would find its fullest expression in the events of the next generation.